By Charlotte Lowrie

Henri Cartier-Bresson spoke eloquently and passionately of using the camera to tell picture stories. Making a picture story, in Cartier-Bresson’s view, required that the photographer’s “the brain, the eye, and the heart” work together to capture an unfolding process. For some photographers, myself included, the heart of photography exists most vibrantly in the picture stories that unfold every day on city streets. Street photography has the singular ability to bring the nightly news to a personal level. When you shoot on the street, people in the news are no longer vague, faceless statistics—they are the people standing next to you on a street corner.

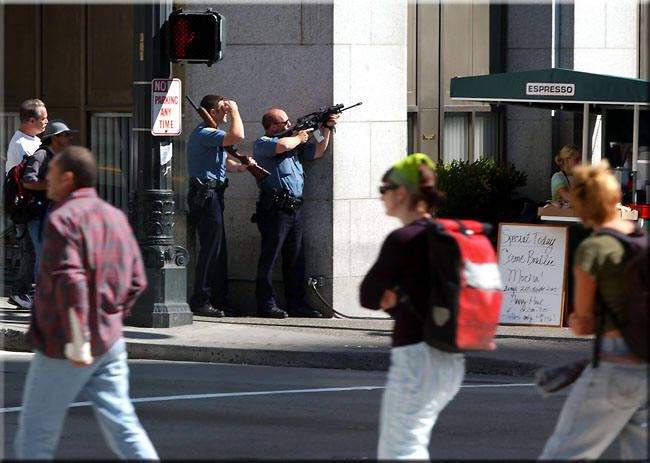

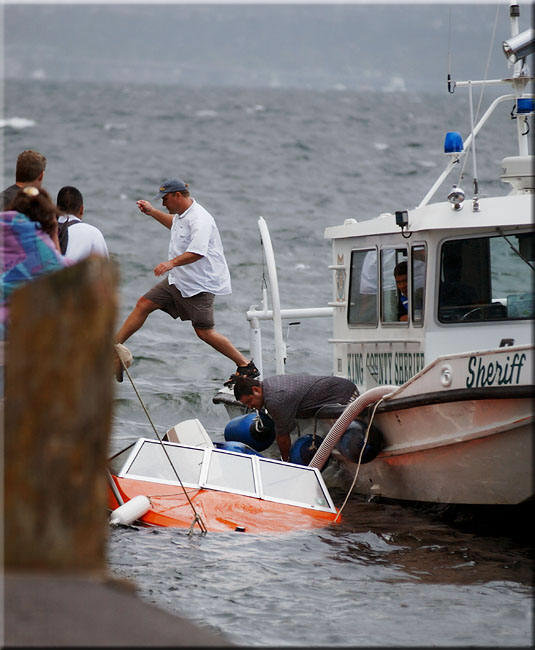

It’s possible to spend months shooting scenes of everyday life on the streets—and it’s equally possible to suddenly find yourself in the center of a developing drama. Purely by chance, for example, I’ve found myself photographing an attempted kidnapping, a deranged sniper aiming a rifle into a courthouse window, and a local sheriff’s water rescue team saving a pleasure boat, along with its terrified occupants, from sinking into the deep, chilly waters of Lake Washington.

When street shooting suddenly becomes a drama, it’s possible to shoot hundreds of images. But the shots count only if you can ultimately tell the whole story—from the first moment to the last “decisive moment” that wraps up the story. Is there a secret to getting a classic picture story? From my experience, the answer is no. Rather for me, making a picture story is a sequence of preparation, finesse, awareness, and, of course, a passion for telling stories.

1. Eyes Wide Open. There is nothing more important in street shooting than having an acute awareness of what’s going on around you at all times. Certainly this awareness helps ensure your personal safety, but more important, acute awareness puts the photographer in touch with the heartbeat of the city—that palpable throb of life in progress that makes street photography compelling and addictive.

1. Eyes Wide Open. There is nothing more important in street shooting than having an acute awareness of what’s going on around you at all times. Certainly this awareness helps ensure your personal safety, but more important, acute awareness puts the photographer in touch with the heartbeat of the city—that palpable throb of life in progress that makes street photography compelling and addictive.

For me the awareness always pays high dividends. After an afternoon of shooting in downtown Seattle, I was ready to pack up and drive home. But my heightened awareness made me pause to look across the street one last time. Among the crowds of pedestrians, I saw two policemen leaning against a building. One policeman had a high-powered rifle trained on an historic hotel that I had photographed only moments earlier. I swung the camera to my eye. With a single glance in the viewfinder, I realized that the pedestrians seemed oblivious to the well-armed officer only steps away. Through the viewfinder, I watched incredulously as pedestrians walked around the officers to buy lattes at the coffee stand directly in front of the policemen.

2. Instinctive exposure. In situations such as this, my internal mantra automatically kicks in telling me to “open up and stay focused on the subject.” I instinctively open up, often shooting an entire sequence at f/2.8 or f/4.0. In the sniper incident, for example, the action moved between bright sunlight on the police side of the street to deep shade on the sniper side of the street. With a wider aperture, I could move from sunlight to shade and be fairly certain of getting sharp handheld images and acceptable exposures in the bright light. Plus, by opening up, background signs, billboards, power lines, and bus cables blur nicely into the background.

2. Instinctive exposure. In situations such as this, my internal mantra automatically kicks in telling me to “open up and stay focused on the subject.” I instinctively open up, often shooting an entire sequence at f/2.8 or f/4.0. In the sniper incident, for example, the action moved between bright sunlight on the police side of the street to deep shade on the sniper side of the street. With a wider aperture, I could move from sunlight to shade and be fairly certain of getting sharp handheld images and acceptable exposures in the bright light. Plus, by opening up, background signs, billboards, power lines, and bus cables blur nicely into the background.

The second half of the mantra is harder--regardless of how heavy a long lens feels after five or 10 minutes, I know that losing focus on the scene risks losing the shots that will ultimately create the color and texture of the story. Of course, another instinctive thought, particularly after a full afternoon of shooting, is how much storage remains on the media card. To ensure uninterrupted shooting, I keep a spare empty media card in my pocket. If a scene develops, I swap in the fresh card at the first break in action.

3. Fading into the scene. As street action develops, police, fire, and security personnel begin to move spectators, business owners, and, of course, photographers back from the scene. This is a good time to have a strategy that ensures the longest amount of close-in shooting time possible. My strategy is to blend in with the business owners, to strike up casual conversations with the officials on the scene, and, most important, to project a sense of being one with the scene. At the same time, I’m careful to not obstruct police as they secure the area. And in the few instances when I’ve been asked who I was and why I was there, I simply say that I’m a freelance photojournalist.

Often safety officials around the perimeter are charged with crowd control. Because they are not directly involved in the action, they are more amenable to keeping the original group of bystanders informed about the situation. This information is invaluable for understanding the story and planning ongoing shots.

4. Unobstructed and safe shooting positions. Getting compelling shots depends in part on a good, unobstructed shooting position. In dangerous situations, the best shooting positions are the places where you can safely stand or kneel without obstructing officials or getting yourself shot or hurt. As I chat with other bystanders and safety officials, I ask about access to interiors positions such as second story windows or roof-tops, if I think that these positions would be better than street-level shooting. Otherwise, I stay where I am and look for unobstructed shooting positions. And if I decide to change position, I move inches at a time so that my movement attracts little or no attention.

4. Unobstructed and safe shooting positions. Getting compelling shots depends in part on a good, unobstructed shooting position. In dangerous situations, the best shooting positions are the places where you can safely stand or kneel without obstructing officials or getting yourself shot or hurt. As I chat with other bystanders and safety officials, I ask about access to interiors positions such as second story windows or roof-tops, if I think that these positions would be better than street-level shooting. Otherwise, I stay where I am and look for unobstructed shooting positions. And if I decide to change position, I move inches at a time so that my movement attracts little or no attention.

For me, as the adrenaline of the event kicks in, an irrational sense of invincibility inevitably follows. Regardless of how invincible I feel, I try not to make sure that my shooting doesn’t become a secondary problem for the police. And when the yellow tape goes up, I move back. However, by becoming acquainted with the officers on the scene, I am usually the last person they ask to move behind the yellow tape.

5. Telling the whole story. Between the first and the last moments of an unfolding event are the moments that tell the whole story. Images of these moments give the story the context of emotion, challenge, and tension. These pictures are the sidebars or the subplots to the unfolding main scene. During these moments, anything can happen; maybe a store owner falls ill, a vagrant threatens to foil police action, or the mother of the suspect steps forward from the crowd. Weaving the subplots into the final picture story is what street shooting is all about to me.

I find lulls in the action to photograph concerned shop owners, wandering street people, and police securing the scene. In non-dramatic street scenes, subplots are equally important in providing context to the story. How do characters in the pictures interact, what is their relationship to the environment, to the city?

I find lulls in the action to photograph concerned shop owners, wandering street people, and police securing the scene. In non-dramatic street scenes, subplots are equally important in providing context to the story. How do characters in the pictures interact, what is their relationship to the environment, to the city?

6. The decisive moment. When I’m shooting on the street, particularly in a dramatic scene, I believe that the decisive moment is the moment of peak tension after which the situation is safely resolved. Getting the picture of critical tension is like adding a period to the last sentence of a novel: Without it, the story isn’t complete. There only secret to getting this shot is being there and being ready. I keep the camera to my eye, and I am prepared to shoot with abandon when the action unfolds. And even if the area is cordoned off, a long lens with an extender can often get you the shot you want. Certainly not all street photography involves dramatic events; in fact, most street photography centers on telling the story of our collective life and times.

But the principles are the same: Finding a compelling scene, and then waiting for the one person to stride into the scene to complete it, to explain it, to add mystery or intrigue to it. Or as Cartier-Bresson wrote, “The photographer must make sure while he is still in the presence of the unfolding scene, that he hasn’t left any gaps, that he has really given expression to the meaning of the scene in its entirety.”

Related articles: